COP16 Highlights: Progress on Updating Ecologically or Biologically Significant Marine Areas (EBSAs) – A Key to Global Ocean Conservation

The just-wrapped-up sixteenth Conference of the Parties (COP16) to the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) yielded a critical milestone for marine conservation: the update of Ecologically or Biologically Significant Marine Areas (EBSAs). This progress represents an important advancement towards achieving the goals of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF), which calls on governments worldwide to protect 30% of marine areas by 2030. As scientific knowledge and environmental conditions continue to evolve, the revised EBSA designations aim to strengthen the scientific foundation necessary for establishing effective Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) and sustainable management practices.

To understand the significance of this update, let’s revisit the concept of EBSAs. These areas are identified based on their critical ecological or biological roles within marine ecosystems, where targeted conservation efforts are essential for sustaining biodiversity and ecosystem health. Originally introduced at COP9 in 2008, the EBSA framework is grounded in rigorous scientific criteria, including uniqueness, the importance to species life cycles, support for endangered species and habitats, vulnerability, sensitivity, and contributions to biological productivity and diversity. This multi-criteria approach ensures that EBSA identification reflects each region's ecological importance and conservation potential.

Since 2011, the CBD Secretariat has conducted regional workshops to refine and expand the EBSA map, a process that has identified 279 areas covering 19% of the global ocean surface by COP14 in 2018. The new updates made at COP16 reflect the latest scientific data, emphasizing a renewed commitment to areas essential for marine biodiversity. These EBSAs vary widely, from vast oceanic regions to small, unique features. Some are static, while others shift seasonally, making them invaluable in guiding conservation priorities, research, and the development of management tools like MPAs, environmental impact assessments, and fisheries regulations.

Updating EBSAs is purely scientific and does not automatically translate into immediate protection or management measures. Specific conservation strategies must still be developed and enacted by governments or intergovernmental bodies. However, identifying these areas lays a solid groundwork for future action, with data-driven insights informing policy decisions that may eventually lead to legally protected zones and targeted sustainability practices.

With accelerating pressures on marine ecosystems and the global push towards the "30x30" target, the protection of EBSAs has become a pressing issue. This need has only intensified following the adoption of the landmark United Nations High Seas Treaty, also known as the BBNJ Agreement (Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction). This treaty provides a framework for conservation in international waters, setting a precedent for cooperation and equity in marine governance. Yet, many questions remain: how will EBSA identification continue in a rapidly changing environment? And in a world increasingly focused on environmental justice, how can we ensure equitable governance of marine resources?

COP16’s EBSA updates symbolize a vital step forward in the shared responsibility to protect our oceans. As nations strive to meet global biodiversity goals, the scientific foundations laid by these updates will be indispensable in realizing sustainable marine management, supporting the health of ecosystems that provide countless benefits to life on Earth.

Having reviewed CBD COP decisions since 2008, I found it’s clear that EBSAs have been a key agenda item at nearly every Conference. The outcomes of COP16 are undeniably positive and promising, yet we must recognize that we remain far from reaching the 2030 goals set by the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (KMGBF) -- let alone the Framework's ambitious 2050 targets.

Actually, in China, I’ve also seen promising progress just before the COP16. On October 8, 2024, I have noticed that a research team from the Institute of Deep-sea Science and Engineering at the Chinese Academy of Sciences published a significant study in Biological Conservation, unveiling the species diversity and key habitats of offshore and deep-diving cetaceans in the South China Sea. This is the first time Chinese scientists have formally identified Important Marine Mammal Areas (IMMAs), a milestone that I believe is crucial for China’s efforts toward the marine conservation goals of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF). This study is rooted in solid evidence and field data. In fact, over 30 years ago, Prof. John MK Wong, a marine biologist from Hong Kong, had identified at least 19 cetacean species in the South China Sea based on field research, museum specimens, and historical records. The latest field-based findings from the Chinese Academy of Sciences now substantiate this biodiversity with fresh scientific evidence, confirming the richness of marine mammal diversity in the South China Sea.

Now, I’m pleased to see that COP16 has agreed on a new, evolved process to identify ecologically or biologically significant marine areas (EBSAs). Since the CBD began work on EBSAs in 2010, this initiative has been crucial in pinpointing the ocean’s most critical and vulnerable areas, though development stalled for over eight years due to legal and political challenges. COP16 has revitalized this effort, establishing updated mechanisms to identify new EBSAs and review existing ones, ensuring that these areas are cataloged with the latest scientific knowledge to inform planning and management.

Looking ahead, as we are on the road to the COP17 which will be held in Armenia in 2026, achieving a balance between the scientific identification of EBSAs and the establishment of legally enforceable protections remains a critical challenge, especially in politically sensitive or economically valuable marine areas. As climate change and human activities intensify, the criteria for defining EBSAs may need to evolve to stay effective and relevant. The new High Seas Treaty (BBNJ Agreement) also brings fresh urgency to this task, raising essential questions about how to ensure fair and equitable governance of EBSAs, particularly in regions beyond national jurisdiction.

——————————————

Note1: This is only the author's personal opinion. Comment and discuss are welcome.

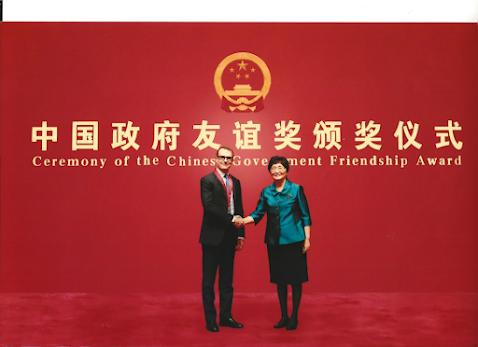

2.The author Linda Wong is the deputy secretary-general of the China Biodiversity Conservation and Green Development Foundation (CBCGDF) , Editor-in-Chief of OceanWetlands, and a member of the IUCN WCPA Marine Connectivity Specialist Group.

——————————————

Author: Linda Wong

Reviewed by: Sara

Editor: Sara

Contact:

v10@cbcgdf.org; +8617319454776

Contribution

Do you know? We

rely on crowd-funding and donations. You have the opportunity to help an

international movement to advance biodiversity conservation. Donate TODAY to

power up the movement to make it a better world for all life.

Donation(501C3)Paypal:

intl@wbag.org

https://www.paypal.com/donate/?hosted_button_id=2EYYJJZ8CGPLE

Comments

Post a Comment